I recently read The 1619 Project by Nikole Hannah-Jones.

It’s a book that has generated legislation in Iowa, South Dakota, Missouri, Arkansas and Mississippi to prohibit schools from teaching The 1619 Project or cut funding from those that do. I needed to understand why the book was banned. I needed to understand the content. The reading was so important for me and it connected puzzle pieces for me as a scholar of the African-American experience, and as an African-American woman.

My parents made me watch Roots (a two-week TV movie about the African-American slavery experience in 1977) at the age of 10, and it made an indelible mark on my psyche (refimled 40 years later in 2016).

To this day, I can still see Cicely Tyson, and I remember images, the beatings, and hearing the crying and wailings. I remember trying to process the why of it all, as a young Black girl. Taking classes in African-American studies at the University of Iowa as a first year student was a start at trying to put puzzle pieces together. I’m still trying.

In college, I majored in English, minored in philosophy and African-American studies. I was reading major writings of African-Americans about history, life, slavery, and music. I remember a History of African-American music, taught by a White man who apologized for being White and teaching Black music. He was an incredible teacher and taught me how to listen to blues, jazz, gospel, rhythm n’ blues. I took a Black poetry class and fell in love with the writings of Nikki Giovanni. I took a Black women’s writers class and fell in love with Alice Walker, bell hooks, Gloria Naylor, and others. Like Nikole Hannah-Jones, I read Before the Mayflower.

https://www.amazon.com/Before-Mayflower-History-America-Revised/dp/0140178228

So, I had a bit of a foundation when I left Iowa.

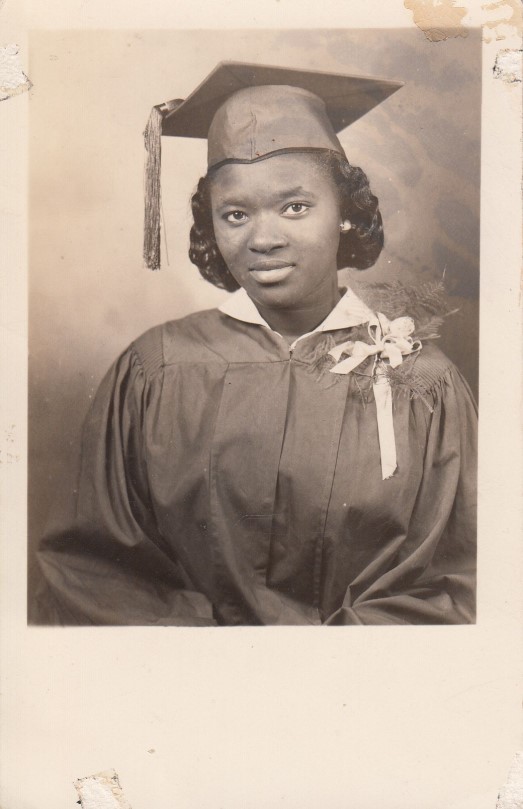

When I went to law school and decided to get a PhD in sociology, I was still piecing together the puzzle of America, of what it meant for me to be African-American: the daughter of a man from Sierra Leone, West Africa, and the daughter of a woman whose grandmother was enslaved.

I taught English Composition at Fisk and the text for the class was Crossing the Danger Water: 300 years of African-American writing. The students and I learned together about what it meant and means to be a Black American. I was starting to feel a bit more empowered, but there was still so much more to learn. I taught English in the men’s and women’s prisons and spent time thinking about America and its history of incarceration and the causes of mass incarceration, especially of African-Americans, men and women, and Nikole reminds us that “Recognizing the unbroken links between slavery, Black Codes, lynching, and … mass incarceration is essential.” p. 282

Getting a PhD in sociology and reading Black Feminist Thought by Patricia Hill Collins

helped me to understand more about being a Black woman in America and the intersectionality of race, class, and gender. Getting a law degree helped me to think about issues of justice, the 14th Amendment, the equal protection clause, affirmative action, equal opportunity.

Over the course of my life, I have thought about and written about Blackness, Whiteness and White supremacy, race and gender. My research and scholarship has been about race, class, and gender, in higher education.

Over the last few years, in so many blog posts, I have wrestled with these issues. I wrote about Dying of Whiteness; I wrote about White Supremacy, and the way in which America has tried to make incompatible ideologies compatible – evidencing a psychosis of incomprehensible proportions.

So, when I finally decided to tackle The 1619 Project, I thought I would be ready. I was just barely ready. And, I don’t know if we can ever get ready and prepare ourselves to understand the full gravity, and impact of learning about America; America’s history; the brutality of slavery; the greed of capitalism; the manifestation of White supremacy; and the inconsistent premise upon which America was founded, as a land of the free and home of the brave, while enslaving millions of Black-skinned people.

The 1619 Project forces a reckoning with reality and the connection between the past to the present. It weaves together America’s complicated history into a quilt that makes sense: connecting democracy, politics, and citizenship, with race, sugar, land, and capitalism. Nikole sews threads of self-defense, crime and punishment, justice, and laws into patches to illustrate the complexity and depth of a structure of White power and privilege and hate and fear. She also affirms the place and power of the Black church as a life-giver and sustainer, in the midst of healthcare policy and practices in the field of medicine that has stolen lives early and often irresponsibly.

“The legacy of this nation to Black Americans has consisted of immorally high rates of poverty, incarceration, and death and the lowest rates of land and home ownership, employment, school funding, and wealth. All of these reveals that Black Americans, along with Indigenous people –the two group forced to be part of this nation—remain the most neglected beneficiaries of the America that would not exist without us.” p. 475.

The “legacy” is a reflection of not only 250 years of enslavement, but almost another 100 years of reimagined enslavement through legalized segregation and violence. As Nikole says, “We have been legally “free” for just fifty years” (p. 35). The gains from the Civil Rights era almost fifty years ago of desegregation were almost systematically severed as “interstates were regularly used to destroy Black neighborhoods,” (p. 408), and busing and school desegregation resulted in the loss of employment for hundreds of Black teachers. On top of that voting rights have continued to shift as efforts are made to obstruct the right of individuals to the ballot.

As Martin Luther King, Jr. said in a 1967 speech, the year I was born, “The fact is that there has never been any single, solid, determined commitment on the part of the vast majority of White Americans to genuine equality for Negroes.” p. 469.

The work ends with a call to justice, a reflection on reparations, and an acknowledgement that “America would not be America without the wealth from Black labor, with Black striving, Black ingenuity, Black resistance. So much of the music, the food, the language, the art, the scientific advances, the athletic renown, the fashion, the guarantees of civil rights, the oratory and intellectual inspiration that we export to the world, … comes forth from Black Americans.” p. 475.

In reading The 1619 Project, I continued to ask myself, chapter after chapter, poem after poem, “Where is the hope”? I had to find hope, even and especially in the midst of so much sorrow, so much pain, so much sacrifice. I had to find the hope to keep on doing the work of DEI. I had to find the hope to understand how to keep persevering and pushing for equity and justice as a way of life. And, I found the hope.

I found the hope in the courage of so many African-Americans who have fought long and hard and arduous battles for our people: Fanny Lou Hamer, Martin Luther King, the Black Panthers, MOVE, Frederick Douglass, Nat Turner, Toussaint Louverture, Denmark Vesey, and so many more.

I found hope in this James Baldwin quote: “not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed unless it is faced” p. 122.

I found hope in understanding and revisiting the power of the Black church as a “forum for righteous anger…and a place of protection and practicality.” p. 339. The Black church and liberation theology have been a beacon with a focus on “a Christian tradition of forgiveness, nonviolence, love, and suffering.” p. 340. These are realities and values that have sustained us as a people.

I find hope in the ability to understand how to redirect anger in an essay about anger: “I started teaching myself to contort my rage into more valuable shapes; it doesn’t disappear that way, just works for you instead of against you. … It was my secret weaponized anger, used for good, that saved me and helped me potentially save a lot of others” p. 397. It affirmed that I can still be angry, very angry, and still love, and still show up committed to justice.

I find hope in Kiese Laymon’s essay on Rainbows: “if believing in rainbows makes us love better, then rainbows can be just as real as work, and love….I can’t stop believing that rainbows are real. How are we ever gonna be free if we only believe the things they tell us are possible?” p. 414. I believe in rainbows.

I find hope in Terry McMillan’s fictional re-enactment of the Greensboro Four — four Black men who stage a sit-in at a white lunch counter: Ezell Blair, Jr., David Richmond, Franklin McCain, and Joseph McNeil. The re-enactment is told from the lens and vantage point of a Black busboy watching the protest and defiance unfold: “they pulled out thick books from their satchels and then se them on the counter, opened them right up like they was all studying the same thing. Where did they get this courage from? Was it from those books? I wondered what they was studying and if there was a class they took on bravery and if they knew other brave colored people. One day I wanted to know what courage felt like, too.” p. 330-331. And at the end of the essay, the busboy, closing up at the end of the long day, sits at the lunch counter, pours himself a cup of coffee, and looks up at the WHITES ONLY sign: “I felt my body rise up and my arms reached up and I pulled it down.” p. 332. I believe we have to be courageous.

We will all need more courage to fight this almost invisible hegemonic energy of capitalism, White supremacy, anti-democracy, racism, sexism, an absence of a commitment to living wage, affordable housing; child care; public education.

I found the hope on pages 363 and 364, in a list of all the musicians that have impacted American music: “decades of jams written, produced, and performed by Black artists sustain parties in places that sustain no actual Black people. This unceasing eruption of ingenuity, invention, intuition, and improvisation constitutes the very core of American culture.” p. 364. Music “born of feeling, of play, of exhaustion, of uncertainty, of anguish, of existential introspection.” p. 378.

Black music “is a testament to a particular kind of pain, and to a unique form of perseverance and self-inquiry. Why us? And how much longer? And what more?…and when? The music testified to a perilous condition as much as it offers hope that, somehow, it will end.” p. 379.

And often Black music is about love, as the essay on Motown indicates. Motown specialized in love songs, challenging “laws, policies, and codes that both stated and implied that Black people were unsuitable for loving, that they were unsuitable for life. Now here was music—popular music, American music—that insisted the opposite was true.” p. 362.

And, I remind myself that I have found hope in ongoing realities in my life. So much of the 1619 Project is about Virginia – the heart of the Confederacy. It was challenging to read about so much of America’s history unfolding almost in my backyard, so to speak. But, I remind myself, even in Virginia, the statues did come down. Even at Virginia Tech, we changed the names of buildings.

https://vtx.vt.edu/articles/2020/08/bov-buildings-resolutions.html

Even at Virginia Tech, we have new markers to tell another story about our history and founding.

https://vtx.vt.edu/articles/2020/08/bov-buildings-resolutions.html

During my reading of The 1619 Project, Serena Williams and Frances Tiafoe gave me hope at the United States Tennis Open. In a stadium of 30,000 largely White Americans, and over 4 million viewers, many were cheering for a Black woman who epitomizes the “American dream,” and who is a living testament to the essence of the spirit of perseverance, persistence, determination of African-Americans. I found hope in Frances Tiafoe and his rise as a child of an immigrant from Sierra Leone, like my father, and his defeat of a tennis champion in Rafael Nadal.

Sports and music have been places of theft and celebration, exploitation and integration, unifying and divisive, yet places of justice, and defining essence of the best of what America should represent in heros like Arthur Ashe, Muhammad Ali, Colin Kapernick, and Tommie Smith and John Carlos, two African-American athletes who each raised a black-gloved fist during the playing of the US national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner,” during their medal ceremony in the Olympic Stadium in Mexico City on October 16, 1968.

16 October 2018 marks the 50th anniversary of one of the most iconic moments in sport, African-American history and the civil rights movement.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/45865645

On this day in 1968, at the Olympic Games in Mexico City, two black U.S. medallists – Tommie Smith and John Carlos – took to the victory stand with their heads bowed and eyes closed, their hands raised with black gloves, and fists clenched. The symbolism of the political statement made by Smith and Carlos had been well planned. The two athletes wore black socks with no shoes to represent “black poverty in a racist America,” while Smith wore a black scarf around his neck, standing for black pride. Carlos also wore beads for those who died due to slavery and raised his left fist to represent black unity. Smith raised his right fist for black power in the U.S. Together, the men represented unity and power.

Their “black power salute” during the playing of the American national anthem was a silent protest by the athletes against racial injustice. Peter Norman, the white Australian sprinter who won the 200m silver medal stood in solidarity with Smith and Carlos. He is often described as the ‘forgotten man’ during the protest, but he had a role to play too. After learning of the American athletes’ plans, Norman is reported to have said: “I will stand with you.”

I found hope in Nikole’s courage to write, to fight, to speak up and out. And Nikole reminds us that we can refuse.

I found hope in remembering her powerful speech at the Faculty Women of Color in the Academy National Conference in April (a conference I founded 10 years ago to empower, support, and connect women of color faculty) where she told almost 800 women of color that we could refuse.

We could refuse to be disrespected, (as she was in the initial denial of tenure from UNC). The 1619 Project reminds us that we can refuse and that as Black Americans we have refused. We have refused to be enslaved, running away, creating insurrections, closing our wombs to prevent impregnation from masters. We have refused to be treated as less than human; we have refused to be denied education; we have refused to be denied the right to vote. We have refused to be silent, and that is often the most important refusal. We have to continue to right and to speak and to read and to educate. Understanding our history is not only important for African-Americans, it is important for all Americans.

I believe that Black communities and churches, in the spirit of Freedom Schools

founded by Marian Wright Edelman and the Abolitionist Teaching Network

https://abolitionistteachingnetwork.org/ founded by Bettina Love,

should create education programs grounded in The 1619 Project. It is important for African-Americans to understand their history.

Equally important, any and every community that believes in the potential of America to live up to ideals for all people, especially allies who emerged during George Floyd, appalled at the hate that African-Americans have addressed for years, should read The 1619 Project. To learn more about The 1619 Project, please visit:

https://pulitzercenter.org/lesson-plan-grouping/1619-project-curriculum